Why Your Cough Won’t Go Away

If you’ve been coughing for more than eight weeks, you’re not alone. About 1 in 10 adults deal with a chronic cough that just won’t quit. It’s frustrating, exhausting, and often doesn’t respond to regular cold remedies. The good news? In most cases, it’s not something serious - but it does need the right kind of attention. The three most common reasons for a long-lasting cough are GERD, asthma, and postnasal drip (now called upper airway cough syndrome). Together, they cause 80 to 95% of chronic cough cases in people who don’t smoke or take certain blood pressure medications.

First Step: Rule Out the Red Flags

Before you start guessing what’s causing your cough, you need to make sure it’s not something dangerous. If you’re coughing up blood, losing weight without trying, running a fever, or have swelling in your legs, you need to see a doctor right away. These could point to lung cancer, infection, or heart failure - not the usual suspects like acid reflux or allergies.

Another thing to check: Are you taking an ACE inhibitor? These are common blood pressure drugs like lisinopril or enalapril. About 5 to 35% of people who take them develop a dry, persistent cough within days or months of starting the medication. If you are, talk to your doctor about switching to a different type of blood pressure pill. Sometimes, just changing the drug makes the cough vanish.

What’s the Minimum Testing You Need?

You don’t need a CT scan, a dozen blood tests, or a sleep study to start. The American College of Chest Physicians says the bare minimum is:

- A chest X-ray - to rule out pneumonia, tumors, or scarring in the lungs

- Spirometry - a simple breathing test that checks for asthma or other lung problems

- A detailed history - when did the cough start? Does it wake you up at night? Do you get heartburn? Do you feel mucus dripping down your throat?

Most family doctors can do these steps in one or two visits. If your chest X-ray is normal and your breathing test looks okay, you’re likely dealing with one of the big three: GERD, asthma, or postnasal drip.

Postnasal Drip (Upper Airway Cough Syndrome)

This is the #1 cause of chronic cough in many adults - and it’s often misunderstood. People think it’s just mucus dripping from the nose into the throat. But it’s really about nerve sensitivity. When your nasal passages are irritated (from allergies, colds, or pollution), they send mixed signals to your brain, making your throat hyper-reactive. Even tiny amounts of mucus can trigger a cough reflex.

The best way to test for it? Try a 2- to 3-week course of an older antihistamine like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) plus a decongestant like pseudoephedrine. Don’t use newer antihistamines like loratadine - they don’t work as well for this. If your cough improves by 70% or more in that time, it’s likely postnasal drip. Most people feel better within 1 to 2 weeks.

Side note: The term “postnasal drip” is being replaced with “upper airway cough syndrome” because it’s not really about the drip - it’s about the cough reflex going haywire.

Asthma - Even If You Don’t Wheeze

Many people assume asthma means wheezing and shortness of breath. But there’s a type called “cough-variant asthma” where the only symptom is a dry, hacking cough - especially at night, after exercise, or when you breathe cold air. It makes up about 24 to 29% of all chronic cough cases.

Standard spirometry might come back normal, even if you have this condition. That’s why doctors often use a methacholine challenge test: you inhale a mist that slightly irritates your airways. If your lung function drops by 12% or more, it confirms asthma. But not every clinic offers this test.

So here’s the practical approach: Try an inhaled corticosteroid (like fluticasone) for 4 weeks. If your cough improves, it’s likely asthma. Some doctors will add a bronchodilator like albuterol if symptoms are worse at night. About 60 to 80% of people with cough-variant asthma respond to this treatment.

GERD - The Silent Culprit

GERD stands for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Most people think of heartburn when they hear that. But here’s the twist: up to 70% of people with GERD-related cough have no heartburn at all. It’s called “silent reflux.” Stomach acid creeps up into the esophagus and irritates the nerves near the voice box, triggering coughing - especially after meals or when lying down.

Testing for GERD is tricky. A 24-hour pH monitor can show acid exposure, but it only catches abnormalities in 50 to 70% of cough patients. That’s why the go-to method is still a therapeutic trial: take a high-dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI) like omeprazole or esomeprazole twice a day for 4 to 8 weeks. No food 3 hours before bed. No coffee, chocolate, or spicy meals.

Here’s the catch: only 50 to 75% of people with GERD-related cough respond. And here’s another twist - up to 40% of people without GERD still feel better on PPIs because of the placebo effect. That’s why newer guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology (March 2024) now say: don’t start PPIs without first ruling out asthma and postnasal drip. If you’ve tried those and still cough, then try the PPI.

What If None of These Work?

Even after testing all three, about 10 to 30% of people still have a cough. That’s when you look at rarer causes:

- Chronic bronchitis (if you’re a smoker)

- Pertussis (whooping cough) - rare in adults, but possible if you haven’t had a booster in 10 years

- Chronic aspiration - swallowing food or saliva into the lungs, common in older adults or those with neurological issues

- Chronic refractory cough (CRC) - where the nerves in the throat are just too sensitive, with no clear trigger

For CRC, a new drug called gefapixant (approved in late 2022) reduces cough frequency by 18 to 22% in clinical trials. Another drug, camlipixant, is under review by the FDA and shows even better results. These aren’t available everywhere yet, but they’re changing the game for people who’ve tried everything.

What to Do Next

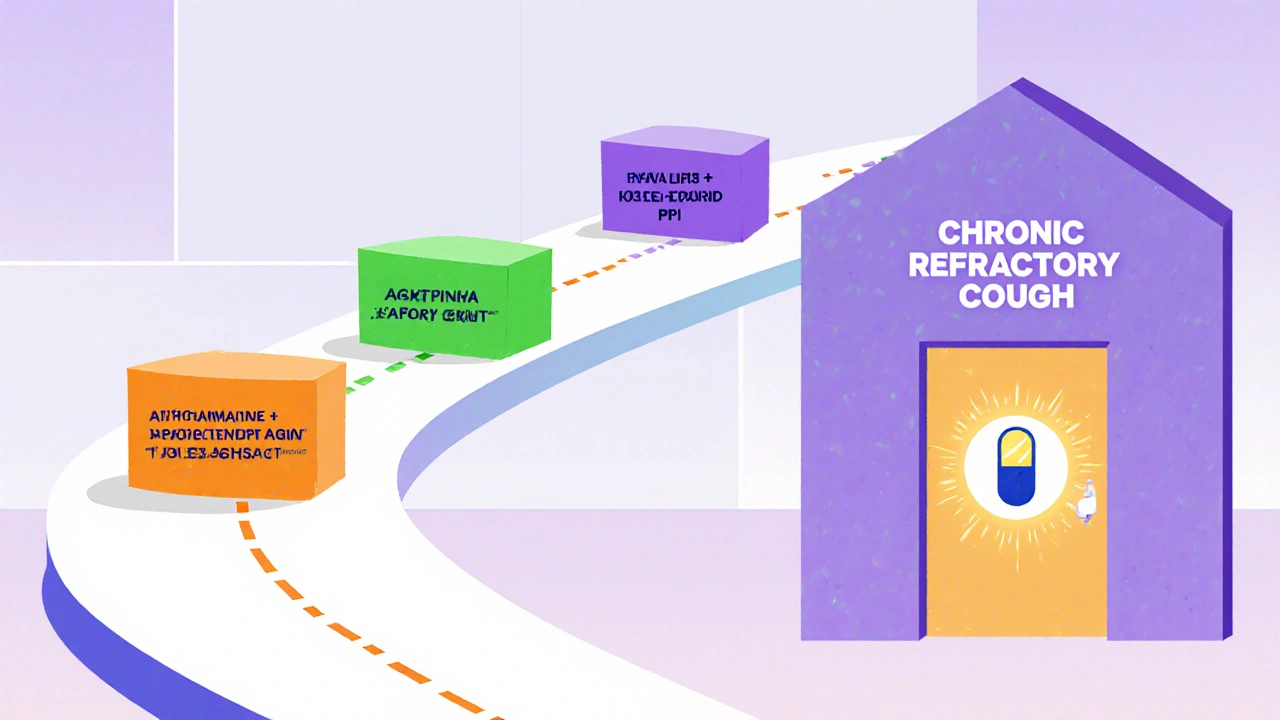

If you’ve had a cough for more than 8 weeks, here’s your simple action plan:

- Stop any ACE inhibitor medications - talk to your doctor first.

- Get a chest X-ray and spirometry.

- If normal, try a 2-week trial of diphenhydramine + pseudoephedrine for postnasal drip.

- If no improvement, try an inhaled steroid for 4 weeks for asthma.

- If still no improvement, try a high-dose PPI twice daily for 8 weeks.

- If still coughing after all that, ask about chronic refractory cough and referral to a pulmonologist.

Don’t waste time on antibiotics - they rarely help. Don’t keep buying cough syrups - they mask symptoms without fixing the cause. And don’t assume it’s “just allergies.” The key is testing one thing at a time, with enough time to see if it works.

How Long Until You Feel Better?

Patience matters. Each treatment needs time:

- Postnasal drip: 1 to 2 weeks

- Asthma: 2 to 4 weeks

- GERD: 4 to 8 weeks

Some people get better faster. Others need longer. If you don’t see improvement by the end of the trial window, move to the next step. Don’t keep taking the same medicine longer - it won’t help if it’s not the right cause.

What About Tests Like CT Scans or Endoscopies?

Don’t jump to these unless you have red flags. A chest CT scan gives you the radiation equivalent of 74 chest X-rays - and finds cancer in only 0.1% of cases where the X-ray was normal. An endoscopy to check your esophagus is rarely needed unless you have swallowing problems or vomiting. Most of the time, it’s overkill.

Instead, focus on the three-step trial approach. It’s cheaper, safer, and works more often than you think.

Final Thought: It’s Not All in Your Head

Chronic cough isn’t psychological. It’s not “just stress.” It’s a real, measurable condition caused by physical irritation - whether from acid, inflammation, or nerve sensitivity. But because it’s invisible and doesn’t show up on scans, many people are told they’re fine - and then left to suffer for months.

The truth is, with the right approach, most chronic coughs can be fixed. You just need to know the order, give each treatment time, and avoid the trap of trying everything at once. Start with the big three. Be systematic. And don’t give up until you’ve ruled them out properly.

Can GERD cause a cough without heartburn?

Yes. Up to 70% of people with GERD-related cough have no heartburn at all. This is called silent reflux. Acid can travel up to the throat and irritate nerves without causing typical stomach symptoms. The cough often happens after meals, at night, or when lying down.

Is postnasal drip the same as allergies?

Not exactly. Allergies can cause postnasal drip, but so can colds, dry air, pollution, or even spicy food. The key isn’t the cause of the mucus - it’s whether the mucus triggers your cough reflex. That’s why treatment focuses on antihistamines and decongestants, not just allergy meds.

Can asthma cause a cough only at night?

Yes. Cough-variant asthma often shows up at night or early morning. This happens because airways naturally narrow during sleep, and lying flat can make inflammation worse. If your cough wakes you up or you need to sit up to breathe, asthma is a strong possibility.

Why do some people get better on PPIs even if they don’t have GERD?

About 35 to 40% of people feel less coughing on PPIs even without acid reflux. This is called the placebo effect - but it’s real. The brain can reduce cough reflex sensitivity just by believing a treatment will work. That’s why newer guidelines warn against using PPIs too early - you might mask the real cause.

What’s the best way to track if my cough is improving?

Use the Hull Cough Questionnaire. It’s a simple 15-point scale that measures how much your cough affects sleep, social life, and daily tasks. A score above 15 means your cough is severely impacting your life. Re-test it every 2 weeks during treatment to see if you’re moving in the right direction.

Josh Gonzales

This is the most practical breakdown I've seen in years. Chest X-ray + spirometry first? Yes. Jumping to CT scans? No. I've seen too many patients get lost in the noise. Stick to the algorithm. It works.

Also, the bit about ACE inhibitors? Lifesaver. I had a patient cough for 11 months until we switched from lisinopril. Gone in 72 hours. Why isn't this in every primary care checklist?