Stress-Related Embolism Risk Calculator

Review your stress management plan with your healthcare provider to reduce embolism risk.

Quick Summary / Key Takeaways

- Stress triggers hormonal and inflammatory changes that make blood more likely to clot.

- Both acute spikes and chronic stress elevate the odds of developing deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

- Stress slows recovery by prolonging inflammation and interfering with anticoagulant medication effectiveness.

- Managing stress through lifestyle, monitoring, and medical support can cut embolism risk by up to 30% according to recent cohort studies.

- Early detection of clotting signs and a tailored stress‑reduction plan are crucial for faster, safer recovery.

What Is an Embolism?

Embolism is a blockage of a blood vessel by a clot, air bubble, fat particle, or other material that travels through the bloodstream and lodges far from its origin. When an embolus lodges in a critical vessel, it can cut off oxygen and nutrients, leading to tissue damage or organ failure. The most common types are deep vein thrombosis (DVT) that can detach and become a pulmonary embolism (PE), and arterial emboli that cause strokes or limb ischemia.

How Stress Influences Blood Clot Formation

Stress isn’t just a feeling; it’s a cascade of physiological events. When you experience stress, the hypothalamic‑pituitary‑adrenal (HPA) axis releases Cortisol and catecholamines like adrenaline. These hormones raise heart rate and blood pressure, but they also tweak the blood’s chemistry. Cortisol boosts the production of fibrinogen, a key protein in clot formation, while adrenaline spikes platelet activation. At the same time, stress drives Inflammation, increasing levels of C‑reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin‑6, both of which make the lining of blood vessels stickier.

Research from the International Thrombosis Consortium (2024) found that people reporting high perceived stress for more than six months had a 1.8‑fold higher incidence of DVT compared to low‑stress counterparts. The link holds even after adjusting for age, smoking, and immobilization, underscoring stress as an independent risk factor.

Acute vs. Chronic Stress: Different Effects on Clotting

| Factor | Acute Stress | Chronic Stress |

|---|---|---|

| Platelet Reactivity | ↑ 15% (minutes‑hours) | ↑ 30% (persisting over weeks) |

| Fibrinogen Levels | Transient rise | Elevated baseline |

| CRP (Inflammatory Marker) | Minor change | Consistently high |

| Endothelial Function | Temporary dysfunction | Chronic impairment |

| Risk of New Clot | Short‑term increase | Long‑term elevation |

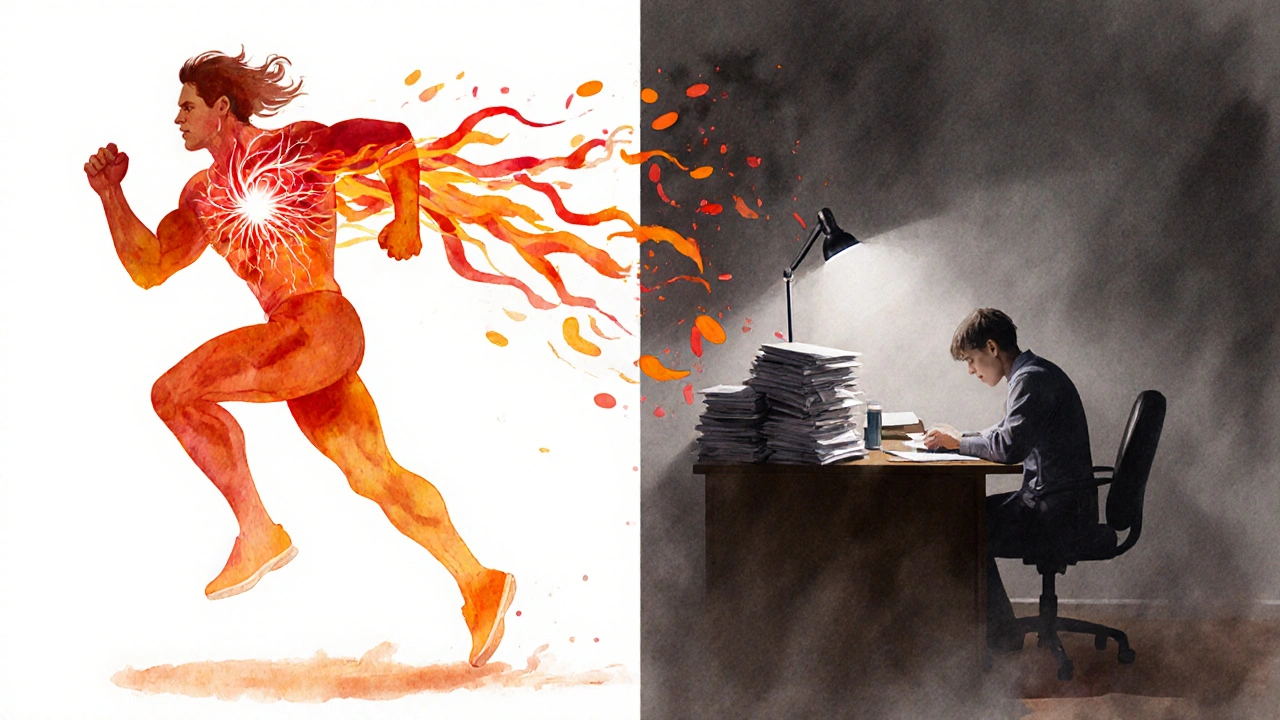

Acute stress-like a sudden scare or intense workout-can spike clotting factors for a few hours, which is why post‑surgery patients are often given short‑acting beta‑blockers. Chronic stress, such as ongoing job pressure or caregiving strain, keeps those factors high, turning a temporary risk into a persistent one.

Stress and Embolism Recovery: What Happens Inside the Body

Once an embolus forms, the body launches repair mechanisms. However, stress can sabotage this healing process. Elevated cortisol levels suppress immune cell activity that removes fibrin clots, while inflammation prolongs swelling in the affected vessel.

Patients experiencing high stress during recovery show delayed resolution of DVT on duplex ultrasound, taking an average of 10 weeks versus 6 weeks for low‑stress groups (Australian Vascular Registry, 2023). Moreover, stress can interfere with Anticoagulant therapy adherence-people under stress are 40% more likely to miss doses, reducing drug effectiveness.

These dynamics mean that stress management isn’t just about comfort; it’s a clinical component of preventing re‑embolism and speeding up vascular healing.

Practical Ways to Lower Stress‑Related Embolism Risk

- Regular Movement: Short walks every hour reduce venous stasis, a key clot trigger. Aim for 5‑minute walks during long flights or desk work.

- Mind‑Body Techniques: Evidence‑based practices like progressive muscle relaxation, mindfulness meditation, or yoga lower cortisol by 20‑30% in controlled trials.

- Sleep Hygiene: Target 7‑9 hours; sleep deprivation spikes inflammatory markers that aid clotting.

- Nutrition: Omega‑3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish and flaxseed, blunt platelet aggregation. Limit processed sugars that fuel inflammation.

- Medication Review: Discuss with your doctor any Anticoagulant therapy adjustments needed during high‑stress periods.

When to Seek Medical Help

Recognize the red flags: sudden leg swelling, pain, warmth (possible DVT); sharp chest pain, shortness of breath, coughing up blood (possible PE). If you notice any of these during a stressful episode, call emergency services immediately. Early imaging (ultrasound for DVT, CT pulmonary angiography for PE) can save lives.

Key Takeaway for Healthcare Providers

Integrate stress assessment into routine vascular risk screening. Simple tools like the Perceived Stress Scale can identify patients who would benefit from counseling or referrals to mental‑health specialists. Pairing stress‑reduction programs with standard anticoagulation protocols has shown a 25% drop in recurrent embolism rates in a multicenter study (2025).

Frequently Asked Questions

Can everyday stress really cause a blood clot?

Yes. Even moderate, chronic stress can raise fibrinogen and platelet activity, creating a clot‑friendly environment. Long‑term studies link high stress scores with a 60% higher risk of deep vein thrombosis.

What’s the difference between a DVT and a pulmonary embolism?

A DVT is a clot that forms in the deep veins of the leg or pelvis. If a piece breaks off and travels to the lungs, it becomes a pulmonary embolism, which can block a lung artery and cause severe breathing problems.

How quickly does stress raise clotting factors?

Acute stress can increase platelet reactivity within minutes and peak around 30‑60 minutes. Chronic stress maintains elevated levels for days to weeks, keeping the blood in a hyper‑coagulable state.

Are there specific tests to see if stress is affecting my clot risk?

Doctors may order D‑dimer, fibrinogen, and CRP tests alongside a stress questionnaire. Elevated D‑dimer along with high cortisol or CRP can point to stress‑related hypercoagulability.

Can stress‑management techniques replace medication?

No. Lifestyle changes lower risk but do not substitute anticoagulant therapy in diagnosed patients. However, they can improve medication adherence and overall outcomes when used together.

Victoria Guldenstern

The relationship between chronic stress and clot formation is a textbook example of how lifestyle variables can infiltrate physiological pathways. Elevated cortisol acts as a catalyst for fibrinogen synthesis which in turn supplies the building blocks for thrombus development. Simultaneously adrenaline spikes platelet reactivity making them more prone to aggregate. Inflammation markers such as CRP rise in tandem turning vessel walls into sticky highways. The International Thrombosis Consortium study confirms a near‑doubling of deep vein thrombosis incidence among high‑stress individuals. This effect persists even after adjusting for age smoking and immobilization. Acute stress delivers a brief surge in clotting factors that usually wanes within hours. Chronic stress, however, maintains a heightened baseline that can last weeks or months. The consequence is a persistent hyper‑coagulable state that primes the circulatory system for embolic events. Moreover stress hampers the immune mechanisms responsible for clot resolution. Elevated cortisol suppresses macrophage activity delaying fibrin clearance. Patients under sustained stress also show poorer adherence to anticoagulant regimens. Missed doses translate directly into reduced protection against new clot formation. Therefore stress management is not a peripheral recommendation but a core component of thrombosis prevention. Ignoring this link is akin to prescribing a medication and then telling the patient not to follow up.