Two kids come home from school with red, crusty sores around their noses. A neighbor wakes up with a swollen, hot patch on their leg that’s spreading fast. Both have skin infections-but they’re not the same. One is impetigo, the other is cellulitis. Mistake one for the other, and you could miss the mark on treatment-or worse, let a serious infection get out of control.

What Impetigo Really Looks Like

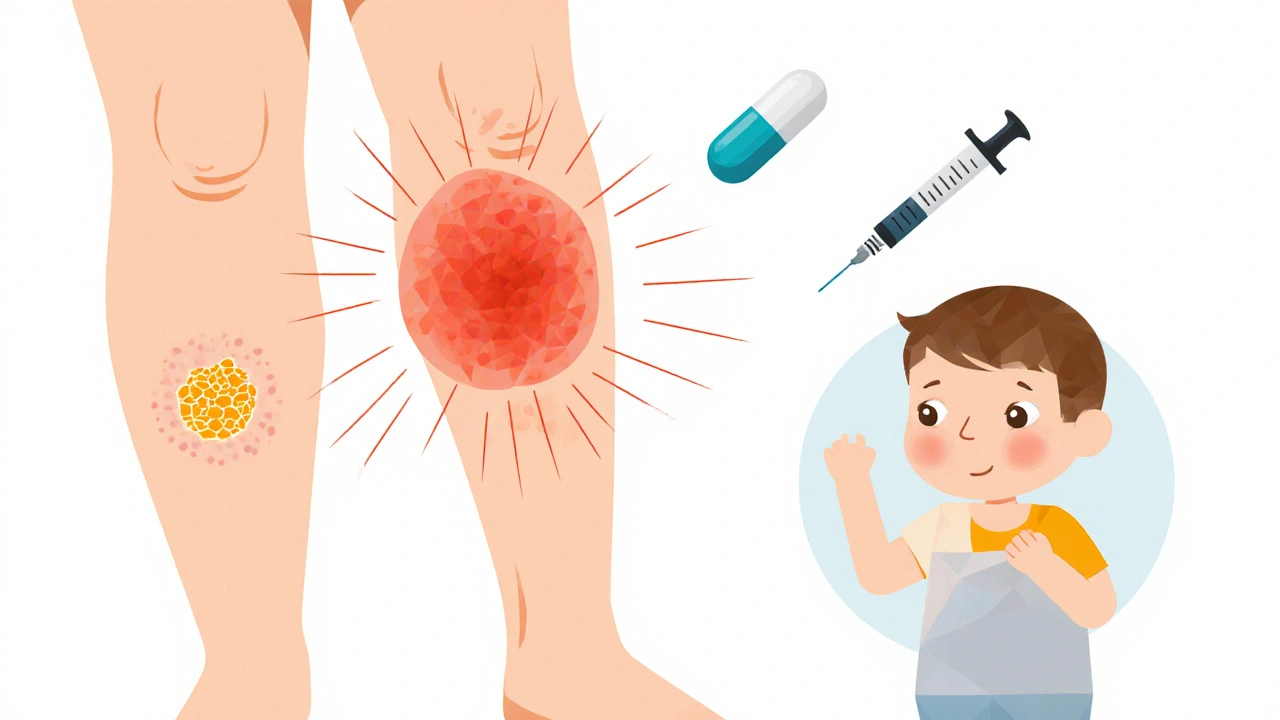

Impetigo is the classic "school sores" infection. It’s common in kids, especially between ages 2 and 5, but adults can get it too-especially if they have eczema, insect bites, or cuts that haven’t been cleaned. The most common type, nonbullous impetigo, starts as small red spots that quickly turn into blisters. These burst, ooze, and then form a sticky, honey-colored crust. You’ll often see them around the nose and mouth, but they can pop up anywhere the skin is broken.

The other form, bullous impetigo, is less common. It shows up as larger, fluid-filled blisters-2 to 5 centimeters across-that look like they’re about to pop. When they do, they leave behind a thin, ring-like edge of skin. These blisters are filled with clear or yellow fluid and are usually painless, which can make them easy to ignore.

What causes it? Mostly Staphylococcus aureus, sometimes Streptococcus pyogenes. It spreads like wildfire in daycare centers and classrooms. One child scratches a sore, touches a toy, and the next kid picks it up. It’s not dangerous on its own, but it’s contagious. Health guidelines say kids should stay home until 24 hours after starting antibiotics. Without treatment, it can last weeks-and sometimes lead to scarring or kidney issues.

Cellulitis: When the Infection Goes Deeper

Cellulitis is a different beast. It doesn’t just sit on the surface. It burrows into the deeper layers of skin and fat, sometimes reaching muscle. It’s not as visible in its early stages as impetigo, but it’s more serious. You’ll notice a red, swollen, warm patch on the skin-usually on the legs, arms, or face. The edges are blurry, not sharp. It hurts. It feels tight. Sometimes it leaks fluid, and you might feel feverish or tired.

Unlike impetigo, cellulitis doesn’t form crusts or blisters. It’s more like a bad sunburn that keeps growing. It’s often caused by Streptococcus bacteria, though Staphylococcus can be involved too. People with diabetes, poor circulation, or weakened immune systems are at higher risk. Even a tiny cut, a bug bite, or a fungal infection like athlete’s foot can let bacteria sneak in.

Left untreated, cellulitis can turn into abscesses, blood infections, or even sepsis. That’s why it’s one of the top 28 reasons people end up in the hospital. The average episode lasts 7 to 10 days with antibiotics-but if you wait too long, recovery takes longer and complications rise.

Key Differences: Impetigo vs. Cellulitis at a Glance

It’s easy to confuse them, especially if you’re not a doctor. Here’s how to tell them apart:

| Feature | Impetigo | Cellulitis |

|---|---|---|

| Depth of infection | Superficial (top layer of skin) | Deep (dermis and subcutaneous tissue) |

| Appearance | Honey-colored crusts or fluid-filled blisters | Red, swollen, warm patch with blurry edges |

| Pain | Mild or none | Significant tenderness, burning |

| Common locations | Face, hands, arms | Legs, feet, arms |

| Contagious? | Highly contagious | Not contagious to others |

| Typical age group | Children 2-5 years | Adults, especially elderly or diabetic |

| Systemic symptoms | Rare | Fever, chills, fatigue possible |

One more thing: erysipelas looks like cellulitis but has sharp, raised borders and is almost always caused by strep. It’s often on the face and feels hot and fiery. It’s a type of superficial cellulitis-but treated the same way.

Antibiotic Choices: What Works and What Doesn’t

Antibiotics are the main treatment for both, but not all are created equal. The wrong one won’t just fail-it could make resistance worse.

For impetigo, if it’s mild and limited to a few spots, topical mupirocin ointment works in about 90% of cases. Just apply it three times a day for 7-10 days. For more widespread cases, or if the sores are oozing a lot, you need oral antibiotics. In the UK and Belgium, flucloxacillin is the go-to. In France, they’re using amoxicillin-clavulanate more often. But if there’s a history of MRSA-or the infection isn’t improving-doctors may switch to clindamycin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

For cellulitis, oral antibiotics are almost always needed. Flucloxacillin is still first-line in the UK. In the US and parts of Europe, amoxicillin-clavulanate is common because it covers both staph and strep. In France, amoxicillin alone is now used more often for mild cases. But here’s the catch: if you’re allergic to penicillin, alternatives like clindamycin or doxycycline are used.

MRSA is the big worry. It doesn’t respond to flucloxacillin, amoxicillin, or even cephalexin. If you’ve had a skin infection before that didn’t heal, or if you live in a place where MRSA is common, your doctor might skip the usual drugs and go straight to clindamycin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Some hospitals now test for MRSA before prescribing-especially if the infection is getting worse after 48 hours.

When to Worry: Red Flags for Both Infections

Most cases are mild and respond well. But here’s when you need to get help right away:

- Redness spreading quickly-more than a few centimeters in 24 hours

- Fever over 38.5°C or chills

- Severe pain that doesn’t improve with painkillers

- Swelling in the face, neck, or near the eyes

- Red streaks running from the infection site

- Confusion, dizziness, or fast heartbeat

If you see any of these, don’t wait. Go to urgent care or the ER. Cellulitis can turn deadly fast. Impetigo rarely does-but if it spreads to the bloodstream or kidneys, it becomes a medical emergency.

Prevention: Stop It Before It Starts

Both infections thrive on poor hygiene and unclean wounds. Here’s how to cut the risk:

- Wash cuts and scrapes with soap and water immediately

- Keep fingernails short to prevent scratching

- Don’t share towels, clothing, or bedding with someone who has an infection

- If your child has impetigo, keep them home until 24 hours after starting antibiotics

- Manage eczema and athlete’s foot-these are common entry points

- For diabetics: check feet daily. Even a small blister can turn into cellulitis

Handwashing is the single most effective tool. It’s not glamorous, but it stops 70% of transmission.

What to Do If Antibiotics Don’t Work

If after 48 hours the redness is still spreading, or the pain is getting worse, you’re not getting better. That’s not normal. It could mean:

- The bacteria are resistant (like MRSA)

- You need a different antibiotic

- There’s an abscess underneath that needs draining

- It’s not a bacterial infection at all

Don’t just keep taking the same pills. Go back. Your doctor may need to take a swab or do a culture to identify the exact bug. In some cases, an ultrasound or MRI is used to check for deeper infection.

Antibiotic stewardship is key. Overprescribing leads to resistance. That’s why many clinics now avoid antibiotics for mild impetigo unless it’s spreading. And for cellulitis, they’re moving away from broad-spectrum drugs unless they’re sure it’s needed.

What’s Next for Treatment?

Doctors are starting to use faster tests-like PCR panels-that can tell if it’s staph, strep, or MRSA in under 2 hours. That means less guessing and better-targeted treatment. Some research is looking at topical antiseptics that kill bacteria without antibiotics. Others are testing vaccines against staph, though none are ready yet.

One thing’s clear: we can’t keep treating these infections the same way we did 20 years ago. Resistance is rising. The goal now isn’t just to kill the infection-it’s to kill it with the least amount of antibiotics possible.

Can impetigo turn into cellulitis?

Yes, but it’s rare. Impetigo stays on the surface. Cellulitis goes deeper. However, if someone scratches impetigo sores and introduces bacteria into a deeper wound-like a cut or scratch-they can develop cellulitis. That’s why it’s important to keep sores covered and avoid scratching.

Is impetigo contagious after starting antibiotics?

No, not after 24 hours of treatment. That’s why health guidelines say children can return to school or daycare after one full day of antibiotics. Before that, the bacteria are still active and easily spread. After 24 hours, the antibiotic has started killing the bacteria, and transmission drops sharply.

Can you get cellulitis from a bug bite?

Absolutely. Any break in the skin-bug bites, cuts, burns, eczema cracks, even dry skin that splits-can let bacteria in. Staph and strep live on our skin naturally. When the barrier breaks, they can invade deeper tissue. That’s why it’s critical to clean and cover even small wounds.

Do I need a culture for every skin infection?

No, not for every case. For simple impetigo or mild cellulitis in healthy people, doctors often treat based on symptoms. But if the infection doesn’t improve after 2-3 days, if it’s recurrent, or if you’ve had MRSA before, a swab or culture is essential. It tells you exactly what bacteria you’re dealing with-and which antibiotics will actually work.

Are natural remedies like tea tree oil effective?

There’s no strong evidence that tea tree oil, honey, or other natural products can cure impetigo or cellulitis. While some may help soothe mild irritation, they won’t kill the bacteria deep in the skin. Relying on them instead of antibiotics can delay treatment and lead to serious complications. Always consult a doctor before skipping prescribed treatment.

How long does it take to recover from cellulitis?

Most people start feeling better within 2-3 days of starting antibiotics. The redness and swelling usually fade over 7-10 days. But full recovery can take up to 2 weeks. If you’re still swollen or in pain after 5 days, contact your doctor. Some people, especially those with diabetes or poor circulation, need longer courses or even IV antibiotics in the hospital.

Final Thoughts

Impetigo and cellulitis might look similar at first glance, but they’re worlds apart in how they behave and how they’re treated. One is a nuisance. The other is a threat. Getting the right diagnosis means getting the right antibiotic-and avoiding unnecessary drugs that fuel resistance. If you’re unsure, don’t guess. See a doctor. Skin infections don’t wait. Neither should you.

Cynthia Boen

This article is overkill. I’ve had impetigo as a kid-soap and water fixed it. No antibiotics needed. Stop medicalizing everything.