Before 1983, fewer than 10 treatments existed for rare diseases in the U.S. Today, more than 1,000 orphan drugs have been approved. What changed? The orphan drug exclusivity system.

What Is Orphan Drug Exclusivity?

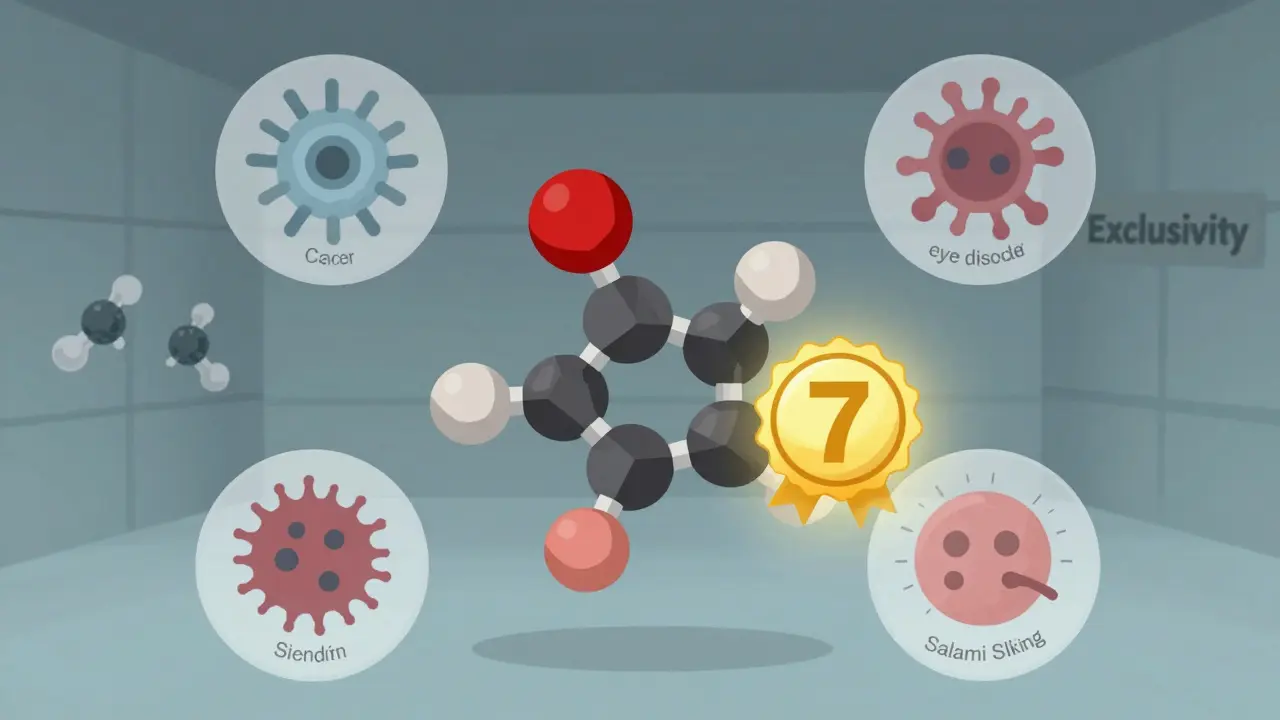

Orphan drug exclusivity is a legal shield granted by the FDA to drugmakers who develop treatments for rare diseases. It gives them seven years of exclusive rights to sell that drug for that specific condition - no matter if someone else has a patent on the same molecule. This isn’t about patents. It’s about market control. The FDA defines a rare disease as one affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. That’s small. For comparison, flu affects 9-45 million people a year. No company could make back its $150 million R&D cost on a drug for 5,000 patients without help. Orphan exclusivity makes it possible.How It Works: The Seven-Year Rule

The clock starts ticking the day the FDA approves the drug for marketing - not when the patent is filed. Once approved, no other company can get FDA approval for the same drug to treat the same rare disease for seven years. Not even if they make it themselves from scratch. There’s one escape hatch: clinical superiority. If another company can prove their version is significantly better - say, fewer side effects, easier to take, or works better - then the FDA can approve it early. But that’s rare. Since 1983, only three cases have met this bar. This system creates a race. Dozens of companies might apply for orphan designation on the same disease. But only the first to finish clinical trials and get FDA approval gets the seven-year window. It’s like a marathon where only the winner gets the prize.Why It’s Different From Patents

Most people think patents are the main way drugs stay protected. But for orphan drugs, that’s often not true. Patents cover the chemical structure or how the drug is made. They can expire in 20 years - but the FDA approval process takes 8-12 years. By the time a drug hits the market, you might have only 8-10 years left on patent life. For rare diseases, that’s not enough to recoup costs. Orphan exclusivity runs parallel to patents. It doesn’t depend on them. Even if the patent expires, the exclusivity still blocks competitors for the orphan use. And unlike patents, which can be challenged in court, orphan exclusivity is automatic once approved. According to IQVIA, in 88% of cases, patent protection was the main barrier to generics - not orphan exclusivity. But for the remaining 12%, orphan exclusivity was the only thing standing between patients and cheaper alternatives.

What’s Protected - and What Isn’t

Orphan exclusivity is narrow. It only protects the drug for the exact disease it was approved for. If a company gets approval for a drug to treat a rare form of leukemia, that doesn’t stop others from using it for common high blood pressure. This has led to a controversial practice called “salami slicing.” Companies apply for orphan status on multiple rare conditions for the same drug. For example, Humira - a blockbuster drug for rheumatoid arthritis - got orphan designation for five rare eye and skin diseases. Even though it’s used by millions for common conditions, it still got seven years of exclusivity for each rare use. Critics say this stretches the intent of the law. The FDA has started pushing back. In 2023, they issued new guidance to clarify what counts as the “same drug” and when multiple orphan designations are justified. But the loophole still exists.How It Compares to Europe

The U.S. gives seven years. Europe gives ten. That’s a big difference. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) also offers a two-year extension if the company tests the drug in children. The U.S. doesn’t. And in Europe, exclusivity can be reduced from ten to six years if the drug turns out to be wildly profitable - something the FDA doesn’t do. The EU is currently reviewing whether to shorten the period to eight years. The U.S. has no plans to change its seven-year rule. Why? Because the system works. In 2022, orphan drugs made up 24.3% of global prescription sales - up from 16.1% in 2018. That growth didn’t happen by accident.Who Benefits - and Who Doesn’t

Patients with rare diseases benefit the most. Before 1983, many had no treatment options. Now, there’s a chance. A 2022 survey by the National Organization for Rare Disorders found 78% of patient groups say orphan exclusivity is essential for getting new drugs developed. But there’s a flip side. Drug prices for orphan drugs are often sky-high. The average annual cost for an orphan drug in the U.S. is over $200,000. Some exceed $1 million per year. While exclusivity helps companies recover R&D costs, it also lets them charge what the market will bear - with no competition for seven years. Generic manufacturers argue this creates artificial monopolies. One executive told the FDA in 2021: “We’ve seen drugs with millions of users get orphan status just to lock out generics.” Regulatory professionals, though, say it’s necessary. A senior biotech manager said in a 2022 forum: “Without orphan exclusivity, we couldn’t justify spending $150 million on a drug for 8,000 people. We’d shut down before we even started.”

How Companies Play the Game

Smart companies start early. They file for orphan designation during Phase 1 or early Phase 2 trials - long before they know if the drug will work. The FDA reviews these applications in about 90 days and approves 95% of them if the disease meets the 200,000-patient threshold. Once designated, they race to complete trials and get approval. The first to finish wins the exclusivity. Many spend 12-18 months building their regulatory strategy, including hiring experts to prove the disease is rare enough. The FDA even offers free pre-submission meetings to help companies navigate the process. Ninety-two percent of companies say these meetings were helpful.The Future of Orphan Drug Exclusivity

By 2027, Deloitte predicts 72% of new FDA-approved drugs will have orphan status. That’s up from 51% in 2018. Oncology leads the way - nearly half of all orphan drugs treat cancer. Neurology, hematology, and metabolism follow. The system isn’t perfect. But it’s working. The orphan drug market hit $217 billion in 2022. That’s more than the entire pharmaceutical market in many countries. The real question isn’t whether orphan exclusivity should exist. It’s how to balance patient access with fair pricing. The FDA is watching. Congress is listening. But for now, the seven-year rule stays.For patients with rare diseases, it’s the only reason new treatments exist. For companies, it’s the only reason they bother. And for the system as a whole, it’s a rare example of policy that actually delivered what it promised.

How long does orphan drug exclusivity last in the U.S.?

In the United States, orphan drug exclusivity lasts seven years from the date the FDA approves the drug for marketing. This protection applies only to the specific rare disease indication for which the drug was designated and approved. No other company can get approval for the same drug to treat the same condition during this period, unless they prove clinical superiority.

Can a drug have both a patent and orphan exclusivity?

Yes. Most orphan drugs have both. Patents protect the chemical structure or manufacturing method and typically last 20 years from the filing date. Orphan exclusivity protects the drug’s use for a specific rare disease and lasts seven years from FDA approval. The two run independently. Even if the patent expires, orphan exclusivity still blocks competitors for that indication.

What’s the difference between orphan designation and orphan approval?

Orphan designation is a formal status granted by the FDA when a drug is still in development and meets the criteria for treating a rare disease. It’s a preliminary step that makes the company eligible for incentives like tax credits and fee waivers. Orphan approval happens later, when the FDA approves the drug for marketing. Only then does the seven-year exclusivity period begin.

Why do some drugs get multiple orphan designations?

Companies sometimes seek orphan status for different rare diseases that the same drug can treat. For example, a drug approved for one rare cancer might also work for a rare autoimmune disorder. Each approval gives a separate seven-year exclusivity period. This practice, called “salami slicing,” is legal but controversial - critics say it extends monopolies beyond the original intent of the law.

Can generic companies ever enter the market before the seven years are up?

Yes - but only under two conditions. First, if they prove their version is clinically superior - meaning it offers a substantial therapeutic advantage like fewer side effects or better effectiveness. Second, if they’re making the drug for a non-orphan use. For example, if a drug has both an orphan indication and a common use, generics can enter for the common use while the original drug keeps exclusivity for the rare disease.

How many orphan drugs have been approved since 1983?

As of October 2023, the FDA has approved 1,085 orphan drugs since the Orphan Drug Act was passed in 1983. That’s up from just 38 in the decade before the law. Over 6,500 orphan designations have been granted, though not all lead to approval.

John Hay

This system isn't perfect, but without it, we'd be back to the 1970s where kids with rare diseases had no shot. Companies won't risk $150 million on 5,000 patients unless they know they can recoup it. The math doesn't lie.