When a brand-name drug hits the market, it doesn’t stay alone for long. But how long it has to itself before generics show up depends on where you are. In the U.S., a company might hold off competitors for over a decade. In the EU, it’s a different clock. And in some countries, generics can’t even look at the data - let alone copy the formula - for years after the patent runs out. This isn’t just legal jargon. It’s what decides whether a life-saving medication costs $500 or $5.

Why Exclusivity Exists - And Why It’s Controversial

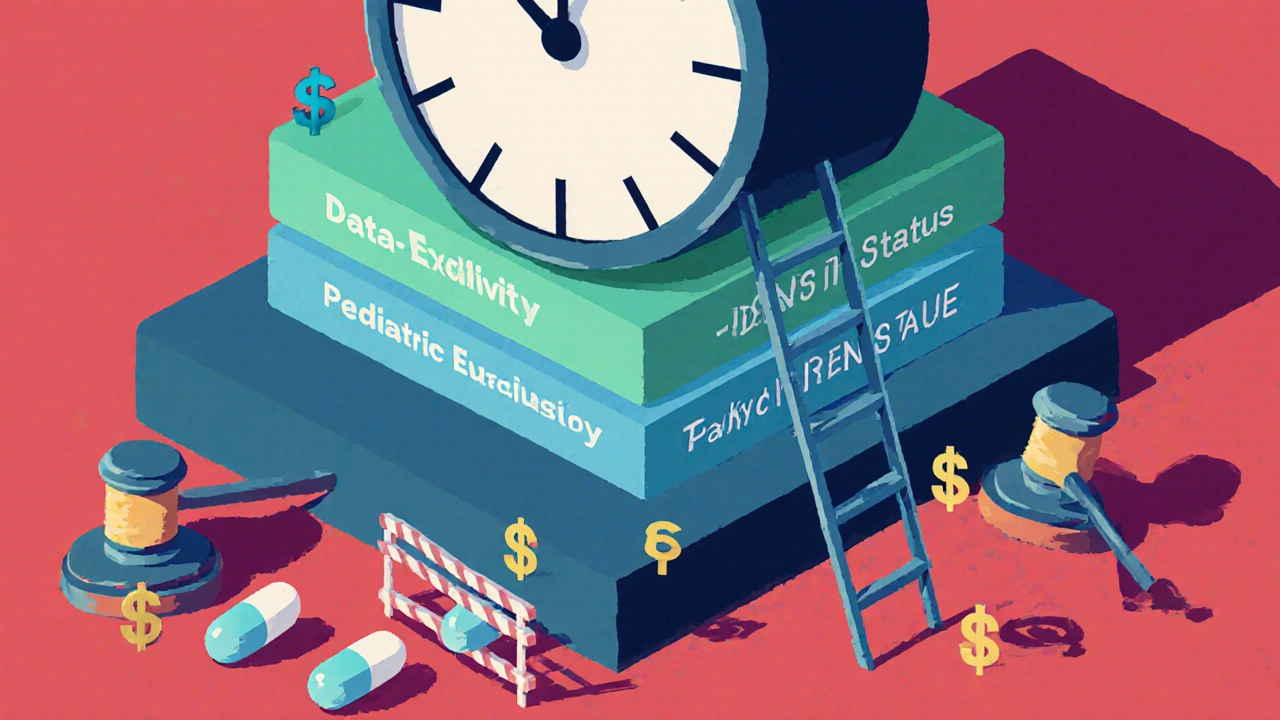

Pharmaceutical companies spend an average of $2.3 billion to bring a single new drug to market, according to Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development. That’s not a guess. It’s based on real R&D costs, clinical trial failures, and years of delays. Without some form of protection, no company would risk it. That’s the theory. The problem? The protection doesn’t always end when the patent does. Patents themselves last 20 years from the filing date - that’s global, thanks to the TRIPS Agreement. But here’s the catch: most drugs take 10 to 12 years just to get approved. So by the time the drug hits shelves, there’s barely 6 to 10 years left on the patent. That’s not enough to recover costs. So countries added extra layers - exclusivity periods - that have nothing to do with patents. These are regulatory tools. And they’re where the real battle happens.The U.S. System: A Maze of Protections

The U.S. is the most complex. It uses a mix of patents, data exclusivity, orphan drug status, and pediatric extensions - all layered on top of each other. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 set up the current system. It gave innovators a 5-year data exclusivity period for new chemical entities. That means no generic can use the originator’s clinical trial data to get approved. But it also gave generics a powerful incentive: the first company to challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusive market access. That 180-day window is a big deal. It’s why companies like Teva and Mylan spend millions on legal teams. They don’t just wait for patents to expire - they file lawsuits to knock them down. If they win, they get to be the only generic on the market for half a year. That’s often enough to capture 80% of the market before other generics arrive. But here’s the dark side: patent thickets. Originator companies now file dozens of patents on minor changes - a new coating, a different pill shape, a tweaked dosage schedule. The FDA’s Orange Book lists up to 142 patents for a single drug. That’s not innovation. It’s legal obstruction. In 2021, Harvard’s Dr. Aaron Kesselheim found that some drugs have an average of 38 additional patents filed after approval. These aren’t new medicines. They’re delays. And then there’s pay-for-delay. Sometimes, the brand-name company pays the generic maker to stay away. The FTC called it anticompetitive. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled it could be illegal. But it still happens. A 2023 survey by the American Pharmacists Association found 78% of pharmacists saw at least three drugs delayed because of these deals.The EU: Predictable, But Slower

The EU doesn’t have the 180-day incentive. It doesn’t have patent challenges in the same way. Instead, it uses an “8+2+1” system. For eight years, no generic can even reference the original company’s data. Then, for two more years, generics can apply - but they can’t sell the drug. Only after 10 years can they enter the market. There’s a possible one-year extension if the original drug showed major new benefits. It’s simpler. It’s more predictable. But it’s also slower. And it doesn’t reward risk-takers the way the U.S. system does. That’s why generic entry in the EU tends to happen right at the 10-year mark - not months before. There’s no race. No jackpot. Just a countdown. The EU also has orphan drug exclusivity - 10 years, extendable to 12. That’s longer than the U.S.’s 7 years. But here’s the twist: the EU’s rules are stricter about what counts as an orphan drug. The U.S. approves more. So more drugs get longer protection there.

Canada, Japan, and the Rest

Canada mirrors the EU. Eight years of data exclusivity, two years of market exclusivity. Simple. Clean. No patent challenges. No 180-day bonuses. Japan is different. It gives eight years of data exclusivity - same as Canada and the EU - but adds four years of market exclusivity. That’s 12 years total. No patent challenges allowed. The system is designed to protect innovation, not to speed up generics. China changed its game in 2020. It extended data exclusivity from six to 12 years. Brazil did something similar in 2021. These are emerging markets trying to attract big pharma. But the cost? Delayed access to affordable medicines. A 2022 WHO report showed that low-income countries wait an average of 19.3 years for generics - nearly eight years longer than high-income countries.What’s Changing? The Push and Pull

The pressure is mounting. In the U.S., lawmakers are trying to ban pay-for-delay deals again with the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act. The EU is proposing to shorten data exclusivity to five years for some drugs. Japan wants to speed up its patent review system. But the industry fights back. PhRMA argues that without these protections, innovation would collapse. They point to the 14% failure rate in Phase III trials. If companies can’t make money on the 1 in 7 drugs that succeed, they won’t try. Meanwhile, access advocates like Dr. Ellen ‘t Hoen say data exclusivity in trade deals like CETA is locking up medicines in poor countries - even after patents expire. HIV drugs in South Africa were delayed by 11 years because of these clauses. The FDA’s former director, Dr. Janet Woodcock, said it best: the agency walks a tightrope. Too little protection, and innovation dies. Too much, and patients can’t afford the drugs.The Real Impact: Prices, Access, and Who Pays

When a generic enters, prices drop 80-90% within a year. That’s not theory. That’s IQVIA data. A drug that costs $1,200 a month becomes $120. Then $40. Then $15. That’s why $356 billion in branded drug sales are at risk between 2023 and 2028. That’s the value of the drugs that are about to go generic. If generics come in fast, insurers and governments save billions. If they’re delayed, patients pay more. Or skip treatment. In the U.S., generics already save $370 billion a year. But that’s only if they get in on time. When patent thickets and pay-for-delay kick in, those savings vanish.What Patients and Providers Should Know

If you’re a patient, don’t assume your drug will go generic when the patent expires. Check if it has data exclusivity. Ask your pharmacist if there’s a legal barrier. If you’re on a chronic medication, plan ahead. A delay of even six months can cost thousands. If you’re a provider, know the difference between patent expiration and market entry. Just because a patent is gone doesn’t mean a generic is available. The regulatory clock is what matters. And if you’re in a country with weak enforcement - like parts of Africa or Southeast Asia - don’t expect timely access. The rules exist on paper. But without strong regulators, generics won’t appear.What’s Next?

By 2027, patent extensions will make up 45% of total exclusivity - up from 32% in 2020. That means even more drugs will be locked up longer. The system is shifting from patent-based protection to regulatory-based control. And that’s harder to challenge in court. The World Health Organization is calling for rebalancing - linking exclusivity to actual R&D costs, not corporate profits. But until then, the rules remain a patchwork. What’s fair in one country is a barrier in another. The bottom line? Generic drugs aren’t just cheaper. They’re a public health tool. And how long they’re kept out of the market isn’t just a legal issue. It’s a human one.How long does a generic drug have to wait before it can enter the market after a patent expires?

It depends on the country and the type of exclusivity. In the U.S., a generic can enter immediately after patent expiration - unless there’s data exclusivity, orphan drug status, or a 180-day exclusivity period held by a first challenger. In the EU, generics can’t even apply for approval until 8 years after approval, and can’t be sold until 10 years. In Japan, it’s 12 years total. Some drugs face delays of 15+ years due to layered protections.

What’s the difference between a patent and data exclusivity?

A patent protects the chemical formula or method of making the drug. Data exclusivity protects the clinical trial data used to prove the drug is safe and effective. Even if the patent expires, a generic can’t use the original company’s data to get approved during the data exclusivity period. That’s why a drug might still be protected even after the patent runs out.

Why does the U.S. have a 180-day exclusivity period for generics?

The 180-day period was created by the Hatch-Waxman Act to incentivize generic companies to challenge weak or questionable patents. The first generic to successfully challenge a patent gets this exclusive window to sell the drug without competition. It’s a financial reward for taking legal risks. But it’s also led to abuse - including pay-for-delay deals where brand companies pay generics to delay entry.

Do all countries have the same exclusivity rules?

No. The U.S. has the most complex system with overlapping protections. The EU uses a fixed 8+2+1 timeline. Canada and Japan have similar but distinct rules. Low-income countries often lack strong regulatory systems, so generics may be delayed even longer - sometimes by trade agreements that force them to adopt stricter rules than they can afford.

Can a drug have both a patent and data exclusivity at the same time?

Yes, and that’s common. A drug might have a patent expiring in 2028, but data exclusivity that lasts until 2032. The generic can’t use the original company’s data until 2032, even if the patent is gone. This means the drug stays protected longer than the patent alone would suggest.

How do pay-for-delay deals affect generic drug availability?

Pay-for-delay deals happen when a brand-name company pays a generic manufacturer to postpone launching its version. This keeps prices high and blocks competition. The FTC estimates these deals cost U.S. consumers over $3.5 billion a year. While courts have ruled them potentially illegal, they still occur - and they’re a major reason why many generics are delayed beyond their legal entry date.

Are there any efforts to shorten exclusivity periods globally?

Yes. The EU is proposing to reduce data exclusivity for some drugs from 8 to 5 years. The U.S. Congress has reintroduced bills to ban pay-for-delay. The WHO recommends aligning exclusivity with actual R&D costs, not corporate profits. But big pharma lobbies hard to keep the current system. Change is slow, and uneven across countries.

Nosipho Mbambo

So let me get this right… we’re paying $500 for a pill because some lawyer filed 142 patents on the color of the coating???

I’m from South Africa-we wait 19 years for generics, and now I see why. It’s not science. It’s corporate theater.

And don’t even get me started on pay-for-delay… that’s just bribery with a white coat.

Meanwhile, my aunt skips her insulin doses because she can’t afford the brand. This isn’t innovation. It’s exploitation.

Why are we still letting this happen? The FDA isn’t protecting patients-it’s protecting profits.

And the EU? At least they’re predictable. Even if it’s slow… at least it’s not a legal minefield.

I’m not anti-pharma. I’m pro-life. And right now, life is priced like a luxury SUV.

Someone needs to break this system. Before more people die waiting for a $5 pill.