Every year, tens of thousands of people end up in the hospital not because their illness got worse, but because the medicine meant to help them made things worse. That’s not rare. In fact, about 6.7% of all hospital admissions in the U.S. are caused by bad reactions to drugs. And here’s the kicker: for many of those people, it wasn’t the doctor’s fault. It wasn’t even the patient’s fault. It was their genes.

What Pharmacogenomics Really Means

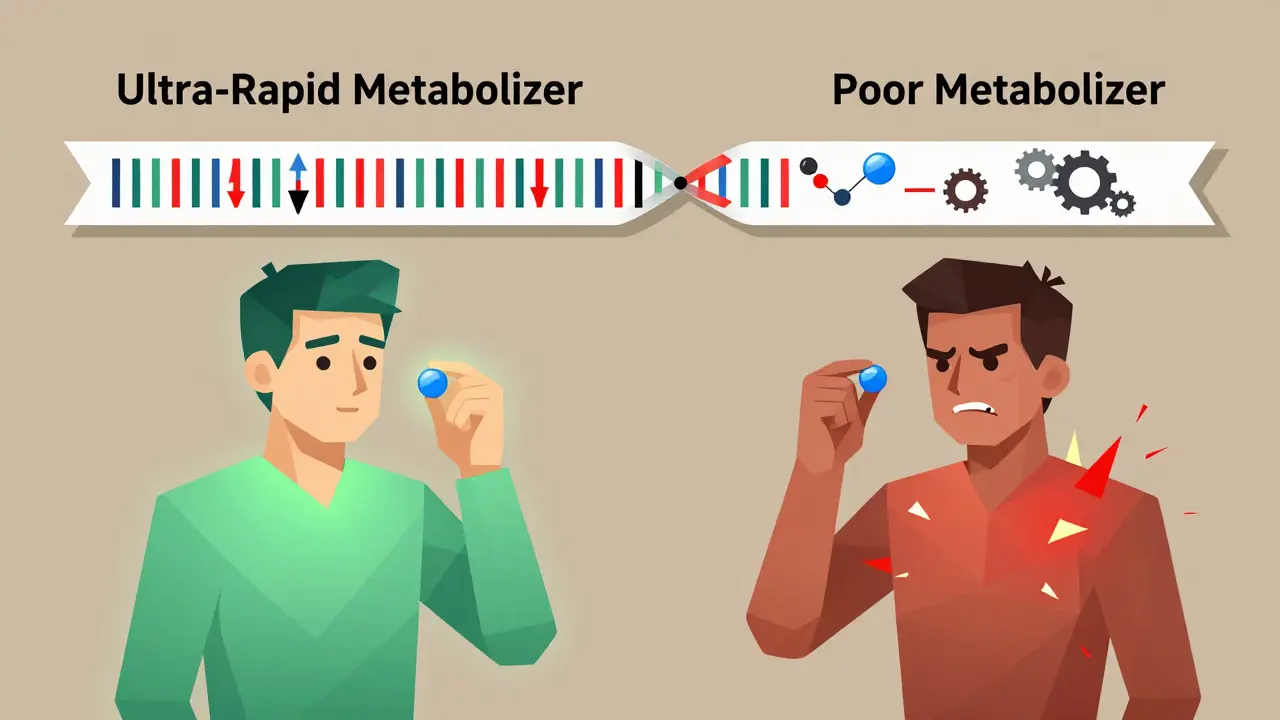

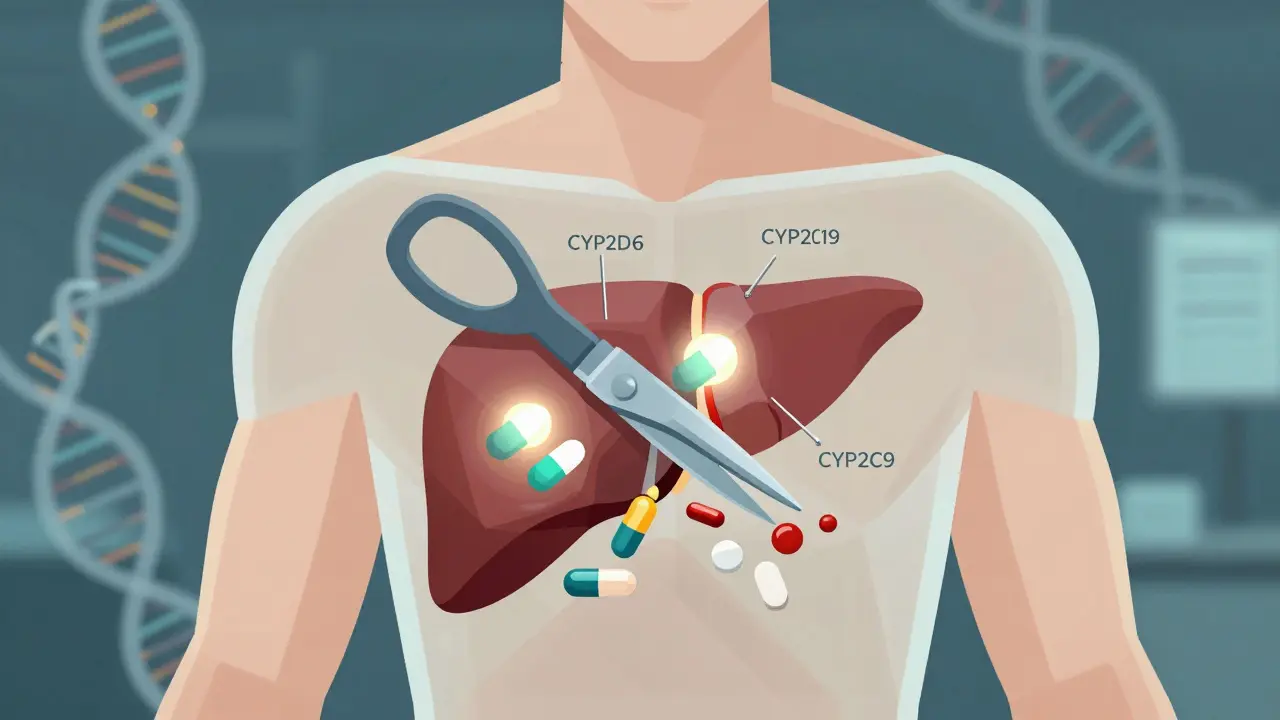

Pharmacogenomics isn’t science fiction. It’s the study of how your DNA affects the way your body handles medicine. Think of it like this: two people take the same pill for depression. One feels better in a week. The other gets dizzy, nauseous, and can’t sleep. Same drug. Same dose. Different results. Why? Their genes are different. This field took off after the Human Genome Project finished in 2003, but the real breakthrough came when scientists started matching specific gene variants to how drugs are broken down-or not broken down-in the body. The big players here are enzymes like CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and CYP2C9. These are liver proteins that act like molecular scissors, chopping up drugs so your body can use or get rid of them. But not everyone’s scissors work the same. Some people have scissors that cut too fast (ultra-rapid metabolizers). Others have scissors that barely work (poor metabolizers). If you’re a poor metabolizer of codeine, for example, your body can’t turn it into morphine. So it does nothing. If you’re an ultra-rapid metabolizer, your body turns codeine into morphine too quickly-and you can overdose on a normal dose. That’s not theoretical. It’s happened to children after tonsillectomies. And it’s why some countries now ban codeine for kids.How Genetic Testing Works

Getting tested is simple. You spit into a tube. Or a nurse swabs the inside of your cheek. That sample goes to a lab, and in about two weeks, you get a report. The test doesn’t look at your whole genome. It looks at 20 to 30 key genes that affect how your body handles the most common medications. The most important genes? CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, and HLA-B. These cover about 70-80% of all clinically meaningful drug-gene interactions. For example:- CYP2D6 affects 25% of all prescription drugs, including antidepressants like fluoxetine, painkillers like codeine, and beta-blockers like metoprolol.

- CYP2C19 handles clopidogrel (Plavix), a blood thinner used after heart stents. If you’re a poor metabolizer, the drug doesn’t work-and you’re at risk for a heart attack.

- HLA-B*15:02 is a gene variant common in people of Southeast Asian descent. If you have it and take carbamazepine (an epilepsy and bipolar drug), you have a 1,000 times higher risk of a deadly skin reaction called Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Where It Works Best

Not every drug needs a genetic test. But for some, it’s life-changing. In psychiatry, the data is strong. A 2022 meta-analysis in JAMA Psychiatry found that patients whose antidepressants were chosen based on genetic testing had a 30.8% remission rate-nearly double the 18.5% rate in those treated the usual way. That means for every 8 people tested and switched to the right drug, one person avoids years of suffering. In oncology, it’s standard. If you have lung cancer, they test your tumor for EGFR, ALK, ROS1 mutations-not because they’re curious, but because those mutations tell them which targeted drug will work. Foundation Medicine found that 15% of cancer patients had actionable gene changes. But only 8.5% actually got the right drug. Why? Insurance denied it. Or the patient was too sick. That’s the gap between science and real life. In cardiology, the story is mixed. Clopidogrel (Plavix) was supposed to be a poster child for pharmacogenomics. Early studies said poor CYP2C19 metabolizers had a 30% higher risk of heart attack. But the big TAILOR-PCI trial in 2020 found no difference in heart events between patients tested and those not tested. Why? Maybe because modern stents are better. Maybe because patients were on other drugs that masked the effect. The new TAILOR-PCI2 trial, with 6,000 patients, is trying to settle this once and for all.

Why It’s Not Everywhere Yet

If this is so powerful, why aren’t all doctors ordering these tests? First, the evidence isn’t there for all drugs. Out of 118 genes that might matter, only 28 are listed on FDA drug labels. And only 12 gene-drug pairs have the highest level of proof (Level 1A). That includes CYP2C19-clopidogrel, CYP2D6-tamoxifen, and HLA-B-carbamazepine. For the rest? It’s still “maybe.” Second, doctors don’t know how to use the results. A 2022 survey found 68% of pharmacists needed extra training to interpret results, especially for genes like CYP2D6, which can have dozens of variants that interact in complex ways. One patient might be a “poor” metabolizer for one drug but an “ultra-rapid” for another. It’s not black and white. Third, the tech doesn’t always plug in. Only 37% of hospitals have successfully linked genetic results to electronic health records. That means a doctor might not even see the test result unless someone prints it out and hands it to them. In one study, 42% of PGx tests ordered didn’t change treatment-because the result got lost in the system. And cost? Testing runs $200-$500. Insurance covers it for cancer drugs, but for antidepressants? Only 47% of commercial plans pay for it. Medicare doesn’t cover it at all for psychiatric use. So even if you want it, you might have to pay out of pocket.Real Stories, Real Impact

One Reddit user, ‘MedStudent2023’, had been on codeine for chronic pain. For six months, they were sick to their stomach every time they took it. They got tested. Turned out they were a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. Codeine wasn’t working. Worse-it was causing side effects. They switched to tramadol. The nausea vanished. They could finally sleep. Another case: a 58-year-old woman in Melbourne had tried seven different antidepressants over 12 years. Nothing worked. Her psychiatrist finally ordered a pharmacogenomic test. Result: she was an ultra-rapid metabolizer of SSRIs. Her body was burning through the drugs before they could work. They switched her to bupropion-a drug not broken down by CYP2D6. Within six weeks, her anxiety lifted. She started gardening again. But not every story ends well. A user on Reddit named ‘GeneticsSkeptic’ got tested through 23andMe. They were an intermediate metabolizer for CYP2C19. Their psychiatrist looked at the report and said, “We’re not changing your sertraline.” Why? Because the evidence for dose adjustments in that specific case wasn’t strong enough. That’s the reality. Not every result changes treatment.

What’s Next

The field is moving fast. The FDA is pushing to require genetic testing for 12 more drugs by 2025-including statins, SSRIs, and warfarin. PharmGKB predicts that by 2027, half of all commonly prescribed drugs will have actionable genetic guidance. That’s up from just 15-20% today. Big players like Thermo Fisher, Myriad Genetics, and Invitae are racing to build better tests. Meanwhile, the NIH’s All of Us program is collecting genetic data from 3.5 million people-including many from underrepresented groups. Right now, 78% of pharmacogenomic studies are based on people of European descent. That’s a problem. A variant that’s rare in Europeans might be common in Africans or Indigenous Australians. Without diverse data, we risk making genetic testing less accurate-or even dangerous-for millions. The goal isn’t to replace doctors. It’s to give them better tools. Pharmacogenomics doesn’t say, “Take this drug.” It says, “Here’s what your body is likely to do with this drug. Let’s choose the safest, most effective option.”Should You Get Tested?

If you’re on three or more medications, especially for depression, anxiety, chronic pain, or heart disease-and you’ve had side effects or no results-you should ask your doctor about testing. If you’re about to start a new drug that’s known to interact with CYP2D6, CYP2C19, or HLA-B, testing before you start could save you months of trial and error. If you’re healthy and just curious? Maybe wait. For now, the biggest benefit is for people already struggling with medication. And if your doctor says, “We don’t do that here”? Ask for a referral to a pharmacist who specializes in pharmacogenomics. Many hospitals now have PGx consult services. In Australia, some private clinics offer testing for under $300. It’s not magic. But for some people, it’s the missing piece.Is pharmacogenomic testing covered by insurance?

Coverage depends on the drug and your plan. Most private insurers cover testing for cancer drugs like tamoxifen or clopidogrel after heart stents. For psychiatric medications, only about 47% of plans pay. Medicare doesn’t cover it for mental health. If you’re paying out of pocket, expect $200-$500. Some labs offer payment plans.

Can I use a direct-to-consumer test like 23andMe?

You can get raw data from 23andMe, but it’s not reliable for clinical decisions. These tests look at a limited set of variants and aren’t validated for drug response. A 2022 study found that 23andMe missed key CYP2D6 variants in 15% of cases. Always use a clinical-grade test ordered by a doctor or pharmacist.

How long does it take to get results?

Most clinical labs deliver results in 10-14 days. Some offer rush testing for $150 extra, with results in 5-7 days. If you’re starting a new medication soon, ask your doctor to order it ahead of time.

Does my genetic data get shared with my insurer?

No. In Australia and the U.S., the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) prevents health insurers from using genetic test results to deny coverage or raise premiums. Employers can’t use it either. Your data is protected. However, life insurance and long-term care insurance are not covered by GINA-so be cautious if you’re applying for those.

Will my doctor know what to do with the results?

Some will. Many won’t. The best approach is to ask for a pharmacist who specializes in pharmacogenomics. Hospitals with PGx programs have pharmacists trained to interpret results and adjust prescriptions. If your doctor is unsure, they can consult the CPIC guidelines-free online tools that tell them exactly what to do for each gene-drug pair.

Is this just for people with chronic illnesses?

No. Even if you’re healthy, if you’re planning to take a drug with known gene interactions-like warfarin, clopidogrel, or certain antidepressants-it’s worth considering. But the biggest benefit is for people who’ve tried multiple drugs without success or had bad side effects. That’s where testing saves time, money, and suffering.

Juan Reibelo

Wow. I’ve been on three antidepressants and two pain meds-each one gave me nausea or brain fog. I got tested last year after my pharmacist pushed me. Turns out I’m a CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizer. Switched to bupropion. No more insomnia. No more nausea. Just… normal. Why isn’t this standard? Why do we still guess with meds?